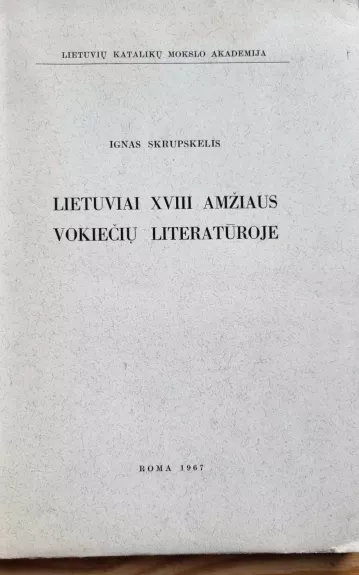

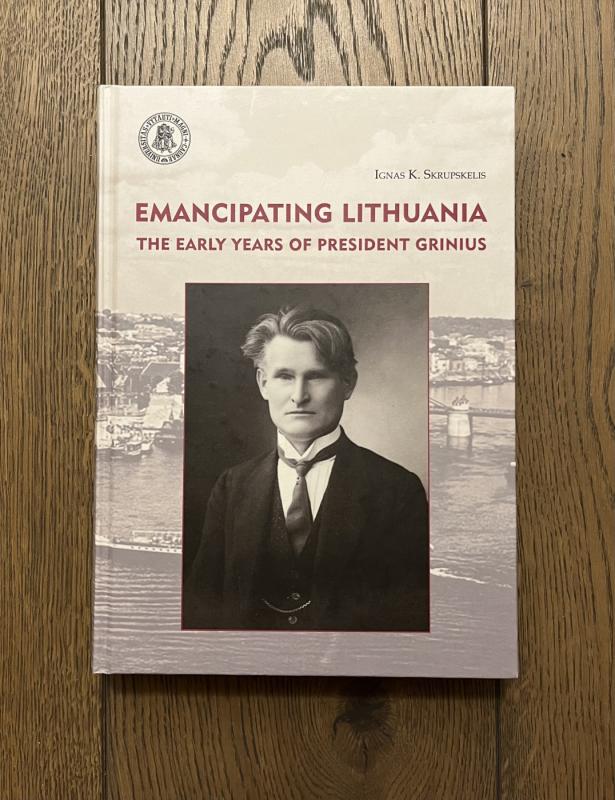

Emancipating Lithuania. The early years of president Grinius

Small nations fare poorly in canonical history. This should not surprise us. After all, small nations are small, that is, lacking resources to develop their own voices and have them heard. Established and generally accepted history is the work of historians of the major powers, reflecting their interests and limitations. A recent example concerns the collapse of the Soviet Union: as far as British Sovietologist Archie Brown is concerned, the important actors were leaders of the great powers. Their motives and actions are important, while unarmed Lithuanian crowds staring down Soviet tanks are forgotten.1 Yet, had it not been for small Latvians, Estonians, Georgians, Lithuanians, the Soviet Union could well have survived. Had nothing changed in those small countries, neither Soviet nor American leaders would have had to consider appropriate responses. My intent and hope, is to allow Lithuania to speak for herself, as the hundredth anniversary of February 16, 1918, the declaration of independence, is upon us. As things stand, the scattered references to her in general histories are by authors who know nearly nothing about her.2 At times, these assertions are merely false, but some are prejudicial and even laughable. In the absence of familiarity, details, there is a tendency to fall back on stereotypes, to do deductive history, ending up in many cases with falsehoods. Developments in these small nations have the misfortune of being categorized as nationalism, while nationalism is often attacked as the cause of wars, conflicts, chauvinism, narrow-mindedness, persecution of minorities. Critics urge that it is much better to celebrate diversity, to use the current American idiom, than to wallow in the petty conceits of one’s tribe. But the emancipators of Lithuania—I suspect of many other nations as well—believed that the rise of small nations was not a barrier to diversity but a condition of it.