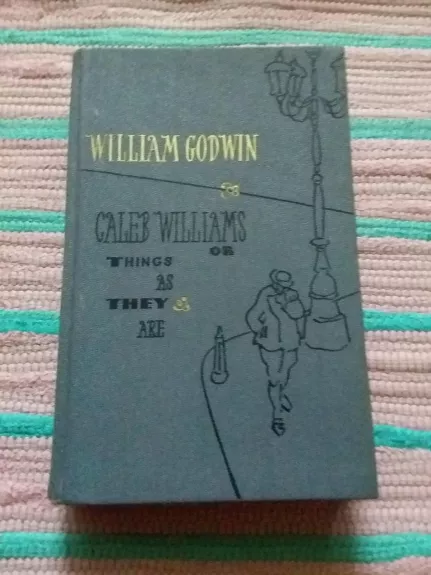

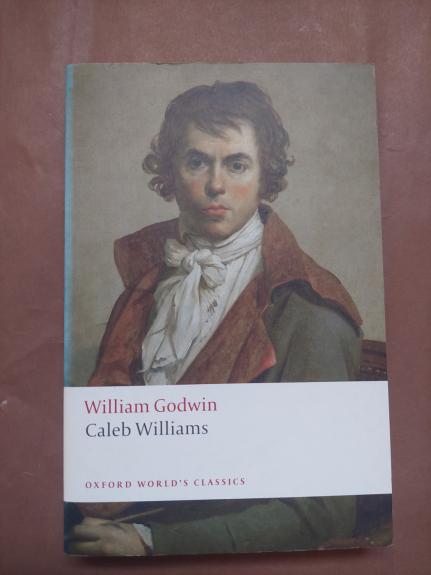

Caleb Williams or Things as They Are

The reputation of WILLIAM GODWIN as a social philosopher, and the merits of his famous novel, "Caleb Williams," have been for more than a century the subject of extreme divergencies of judgment among critics. "The first systematic anarchist," as he is called by Professor Saintsbury, aroused bitter contention with his writings during his own lifetime, and his opponents have remained so prejudiced that even the staid bibliographer Allibone, in his "Dictionary of English Literature," a place where one would think the most flagitious author safe from animosity, speaks of Godwin's private life in terms that are little less than scurrilous. Over against this persistent acrimony may be put the fine eulogy of Mr. C. Kegan Paul, his biographer, to represent the favourable judgment of our own time, whilst I will venture to quote one remarkable passage that voices the opinions of many among Godwin's most eminent contemporaries.

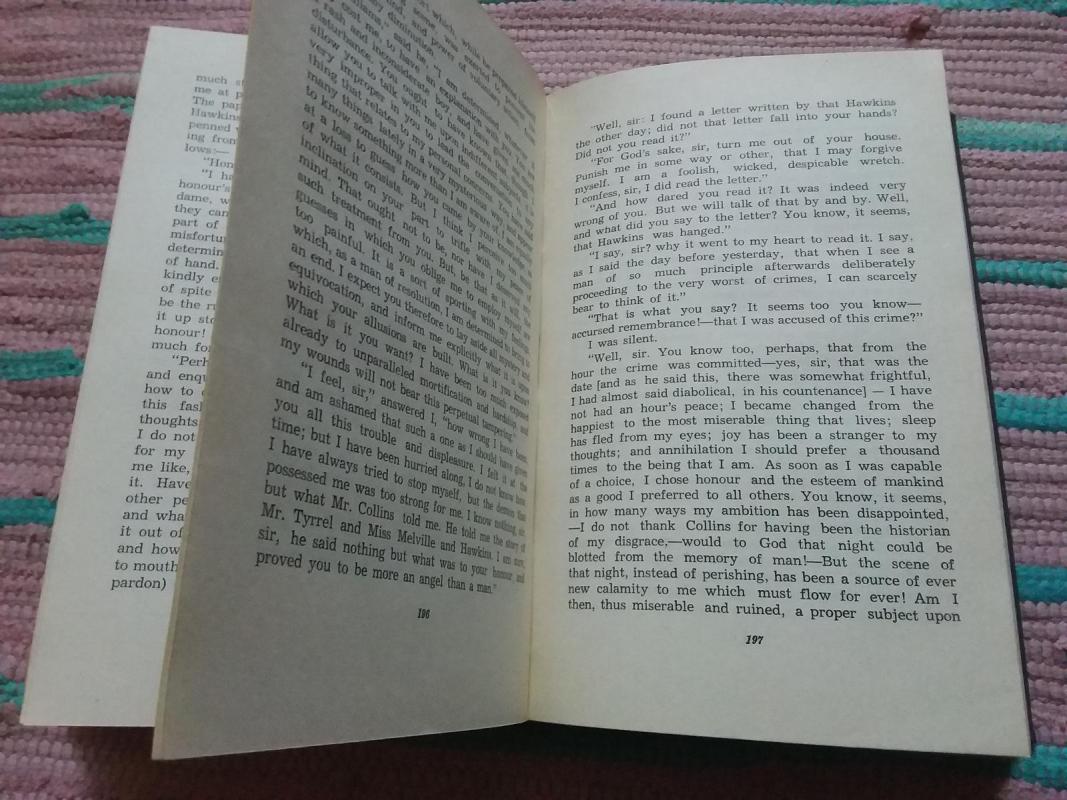

The novel describes the downfall of Ferdinando Falkland, a British squire, and his attempts to ruin and destroy the life of Caleb Williams, a poor but ambitious young man that Falkland hires as his personal secretary. Caleb accidentally discovers a terrible secret in his masters past. Though Caleb promises to be bound to silence, Falkland, irrationally attached (in Godwins view) to ideas of social status and inborn virtue, cannot bear that his servant should possibly have power over him, and sets out to use various means–unfair trials, imprisonment, pursuit, to make sure that the information of which Caleb is the bearer will never be revealed.

Godwin described the book as “a series of adventures of flight and pursuit the fugitive in perpetual apprehension of being overwhelmed with the worst calamities, so that Caleb Williams can be classified as an early thriller or mystery novel.