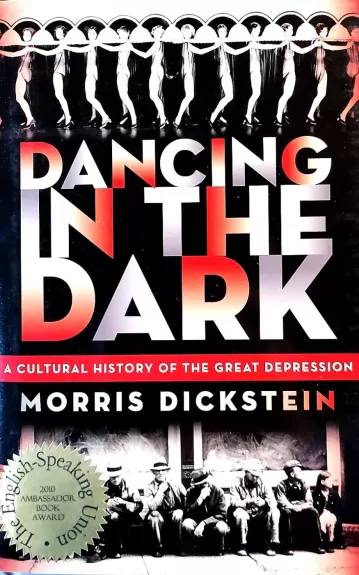

Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression

Only yesterday the Great Depression seemed like a bad memory, receding into the hazy distance with little relevance to our own flush times. Economists assured us that the calamities that befell our grandparents could not happen again, yet the recent economic meltdown has once again riveted the world’s attention on the 1930s.

Now, in this timely and long-awaited cultural history, Morris Dickstein, whom Norman Mailer called “one of our best and most distinguished critics of American literature,” explores the anxiety and hope, the despair and surprising optimism of a traumatized nation. Dickstein’s fascination springs from his own childhood, from a father who feared a pink slip every Friday and from his own love of the more exuberant side of the era: zany screwball comedies, witty musicals, and the lubricious choreography of Busby Berkeley. Whether analyzing the influence of film, design, literature, theater, or music, Dickstein lyrically demonstrates how the arts were then so integral to the fabric of American society.

While any lover of American literature knows Fitzgerald and Steinbeck, Dickstein also reclaims the lives of other novelists whose work offers enduring insights. Nathanael West saw Los Angeles as a vast dream dump, a Sargasso Sea of tawdry longing that exposed the pinched and disappointed lives of ordinary people, while Erskine Caldwell, his books Tobacco Road and God’s Little Acre festooned with lurid covers, provided the most graphic portrayal of rural destitution in the 1930s. Dickstein also immerses us in the visions of Zora Neale Hurston and Henry Roth, only later recognized for their literary masterpieces.

Just as Dickstein radically transforms our understanding of Depression literature, he explodes the prevailing myths that 1930s musicals and movies were merely escapist. Whether describing the undertone of sadness that lurks just below the surface of Cole Porter’s bubbly world or stressing the darker side of Capra’s wildly popular films, he shows how they delivered a catharsis of pain and an evangel of hope. Dickstein suggests that the tragic and comic worlds of Broadway and Hollywood preserved a radiance and energy that became a bastion against social suffering. Dancing in the Dark describes how FDR’s administration recognized the critical role that the arts could play in enabling “the helpless to become hopeful, the victims to become agents.” Along with the WPA, the photography unit of the FSA represented a historic partnership between government and art, and the photographers, among them Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, created the defining look of the period.

The symbolic end to this cultural flowering came finally with the New York World’s Fair of 1939–40, a collective event that presented a vision of the future as a utopia of streamlined modernity and, at long last, consumer abundance. Retrieving the stories of an entire generation of performers and writers, Dancing in the Dark shows how a rich, panoramic culture both exposed and helped alleviate the national trauma. This luminous work is a monumental study of one of America’s most remarkable artistic periods. 24 illustrations